The Effect of Consistency on Corporate Net Income

Testing the Lindy effect

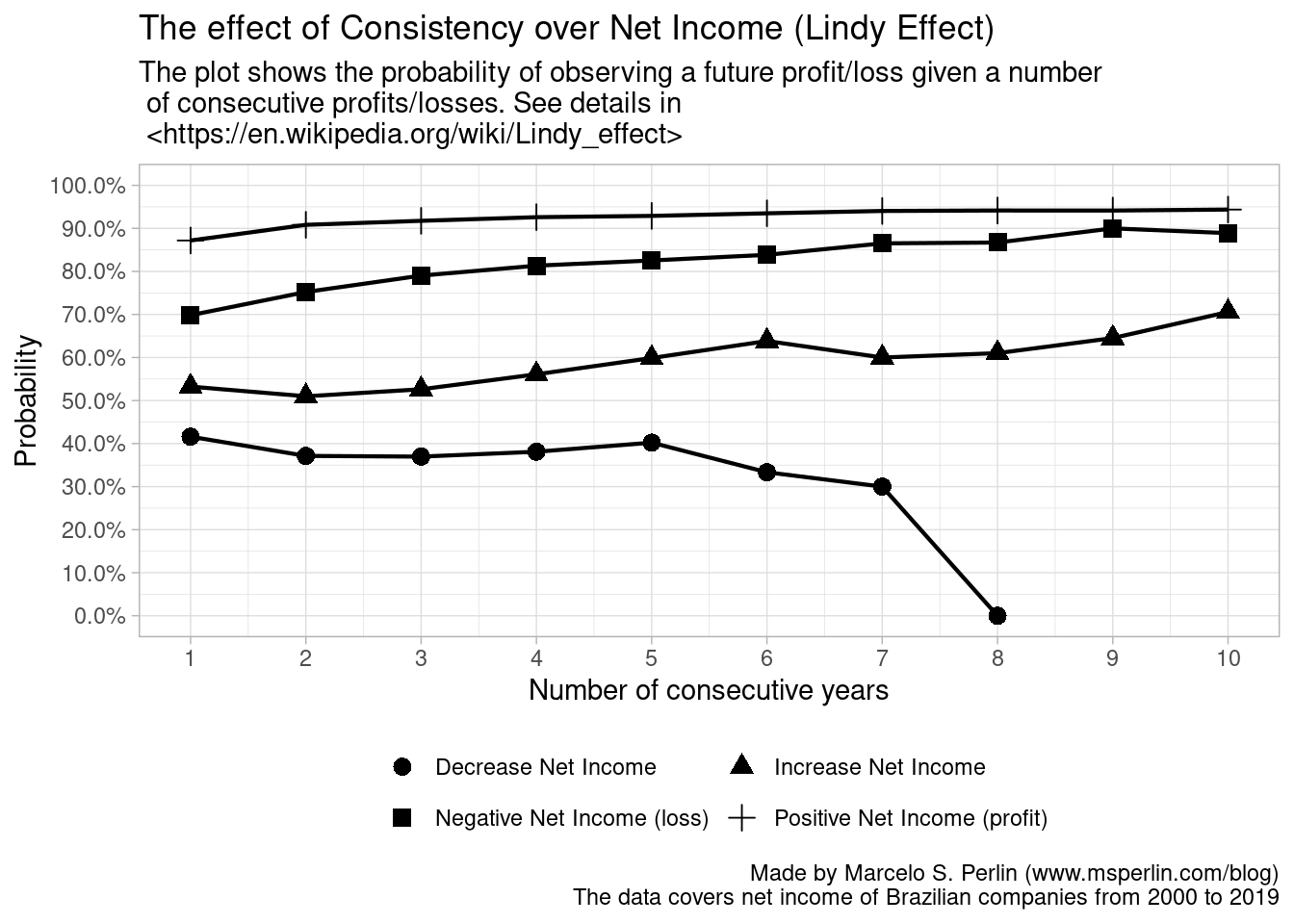

One of the investment concepts that every long term investor should know is the effect of consistency over corporate performance. The main idea is that older and profitable companies are likely to continue to be profitable and even improve its performance in the upcoming years. Likewise, companies with constant losses are likely to continue in the same path.

This idea is related to the Lindy Effect. Quoting directly from wikipedia:

The Lindy effect is a theory that the future life expectancy of some non-perishable things like a technology or an idea is proportional to their current age, so that every additional period of survival implies a longer remaining life expectancy.

As you should suspect by now, I am going to test this idea by looking at the predictive effect of consistent net profits/losses for companies traded at B3, the Brazilian financial exchange. First, let’s import the data and take a glimpse at it.

library(tidyverse)

library(readxl)

my.f <- '~/Dropbox/03-Computer Code/01-R Code/02-Finance Code/Lindy effect on profit/data/LL.xlsx'

df <- read_excel(my.f) %>%

glimpse()## Rows: 6,592

## Columns: 3

## $ id <chr> "AALR", "AALR", "AALR", "AALR", "AALR", "ABCB", "ABCB", "A…

## $ year <dbl> 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008…

## $ net_income <dbl> -4, -11, 29, 15, 52, 53, 58, 61, 83, 137, 151, 202, 235, 2…The structure is straightforward. The data was obtained from a financial portal1 and already organized in a long format, saving myself from the work of restructuring it. As for the columns, it is all very basics. We have company’s id, year and net income.

Next I’ll write a function that will do all the dirty work. The idea is to calculate, for each year/company/horizon, the cases where we find a particular result based on \(k\) results from the past. Confusing right? Let me try again. For example, let’s say you observe at a particular time \(t\) that a company performed the five past years with profits. What we want to know is if such a information can predict the profit in the next year.

In other terms, conditional on the information about past results, what is the likelihood that the next net income will also be positive? By answering this question for every possible horizon, we can build a figure that relates the probability with the time consistency. If the Lindy effect is true for companies, we should see a positive association, that is, the longer the horizon of consecutive results, higher the chances of the same result.

The code for the function is set below.

fct_prob_calc_LL <- function(y, years, company) {

require(tidyverse)

nT <- length(y)

df.res <- tibble()

for (i.year in 2:length(years)) {

lags.to.test <- 1:(i.year-1)

for (i.lag in lags.to.test) {

test.vec <- y[(i.year-i.lag):(i.year-1)]

my.test1<- all(test.vec > 0)

my.result1 <- y[i.year] > 0

my.test2<- all(test.vec < 0)

my.result2 <- y[i.year] < 0

my.test3<- all(na.omit(diff(test.vec) > 0))

my.result3 <- y[i.year] - y[i.year-1] > 0

my.test4<- all(na.omit(diff(test.vec) < 0))

my.result4 <- y[i.year] - y[i.year-1] < 0

df.res <- bind_rows(df.res,

tibble(company = company[1],

year = years[i.year],

horizon = i.lag,

type.test = c('Positive Net Income (profit)',

'Negative Net Income (loss)',

'Increase Net Income',

'Decrease Net Income'),

test.flag = c(my.test1, my.test2,

my.test3, my.test4),

result = c(my.result1, my.result2,

my.result3, my.result4)) )

}

}

return(df.res)

}And now we use it for all companies:

library(purrr)

library(furrr)

l.args <- list(y = split(df$net_income, f = df$id),

years = split(df$year, f = df$id),

company = split(df$id, f = df$id))

plan(multisession(workers = 10))

# get results

tab.test <- bind_rows(future_pmap(.l = l.args, .f = fct_prob_calc_LL,

.progress = TRUE)) %>%

mutate(years = factor(year) ) ##

Progress: ──────────── 100%

Progress: ─────────────────── 100%

Progress: ──────────────────────────── 100%

Progress: ───────────────────────────────────── 100%

Progress: ───────────────────────────────────────────── 100%

Progress: ───────────────────────────────────────────────── 100%

Progress: ────────────────────────────────────────────────── 100%

Progress: ────────────────────────────────────────────────── 100%

Progress: ────────────────────────────────────────────────── 100%

Progress: ─────────────────────────────────────────────────── 100%# build prob table

tab <- tab.test %>%

filter(test.flag == TRUE) %>%

group_by(horizon, type.test) %>%

summarise(prob = mean(result, na.rm = TRUE),

n = n(),

n.companies = length(unique(company)))And finally build the plot with ggplot2:

p <- ggplot(tab %>%

filter(horizon <= 10), aes(x = horizon,

y = prob, group = type.test)) +

geom_point(aes(shape= type.test), size = 3) + geom_line(size = 0.75) +

#facet_wrap(~type.test, nrow = 2) +

labs(x = 'Number of consecutive years',

y = 'Probability',

title = 'The effect of Consistency over Net Income (Lindy Effect)',

subtitle = str_c('The plot shows the probability of observing a future profit/loss given a number \n',

' of consecutive profits/losses. See details in \n',

' <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lindy_effect>'),

caption = str_c('Made by Marcelo S. Perlin (www.msperlin.com)\n',

'The data covers net income of Brazilian companies from 2000 to 2019') ) +

scale_y_continuous(labels = scales::percent,

breaks = seq(0, 1, by = 0.1), limits = c(0,1)) +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = min(tab$horizon):max(tab$horizon)) +

theme_light() + #scale_shape_discrete(name = 'Legenda') +

theme(legend.title = element_blank(), legend.key.size = unit(1,"line"),

legend.position = 'bottom') +

guides(shape=guide_legend(nrow=2,byrow=TRUE))

print(p)

Let me summarize the main conclusions from the plot:

- Time is an ally to the profit of the company. The more consistent the company was in producing profit in the past, higher the chances of a profit in the future.

- Net losses also cluster, but with a lower probability than profits. Notice how the line for losses is always below the line for profits. This means that company with past losses for a given horizon has more chance to turn a profit than a company that shows consecutive profits to turn a loss.

- Changes in net income also have persistence memory, specially for increases. Companies that have increasing profits are likely to continue to increase its earnings. Notice, however, that the probability of increased net income is distributed between 50% and 70%, much lower than for the chance of a positive net income.

- Companies with repeated decreases in its net income are more likely to turn an increase than to continue to decrease (see line at bottom of chart). Notice also that the code can’t find cases for a company with nine or more year of decreases in profit to exist. These are the companies that were bought or bankrupted.

The message from the data and the analysis is clear. In the corporate world, financial inertia is the rule, not the exception. Good and profitable companies continue to be good and profitable enterprises, while bad and unprofitable companies also continue in the same path.

From the investment point of view, the results suggests that time is a friend of the investor. Overall, companies tend to improve its earnings. This corroborates the results from a previous post, where I analyzed the effect of the investment holding period over nominal and real returns to the investor. In short, the more time you stay in the market, the better.

Unfortunately I cannot distribute this structured dataset as it was one of the restrictions on receiving and publishing results based on it.↩︎