Studying CRAN package names

Setting a name for a CRAN package is an intimate process. Out of an infinite range of possibilities, an idea comes for a package and you spend at least a couple of days writing up and testing your code before submitting to CRAN. Once you set the name of the package, you cannot change it. Your choice index your effort and, it shouldn’t be a surprise that the name of the package can improve its impact.

Looking at package names, one strategy that I commonly observe is to use small words, a verb or noun, and add the letter R to it. A good example is dplyr. Letter d stands for dataframe, ply is just a tool, and R is, well, you know. In a conventional sense, the name of this popular tool is informative and easy to remember. As always, the extremes are never good. A couple of bad examples of package naming are A3, AF, BB and so on. Googling the package name is definitely not helpful. On the other end, package samplesizelogisticcasecontrol provides a lot of information but it is plain unattractive!

Another strategy that I also find interesting is developers using names that, on first sight, are completely unrelated to the purpose of the package. But, there is a not so obvious link. One example is package sandwich. At first sight, I challenge anyone to figure out what it does. This is an econometric package that computes robust standard errors in a regression model. These robust estimates are also called sandwich estimators because the formula looks like a sandwich. But, you only know that if you studied a bit of econometric theory. This strategy works because it is easier to remember things that surprise us. Another great example is package janitor. I’m sure the you already suspects that it has something do to with data cleaning. And you are right! The message of the name is effortless and it works! The author even got the privilege of using letter R in the name.

While I can always hand pick good and bad examples, let’s dig deeper. In this post, we will study the names of packages available in CRAN by comparing them to the whole English vocabulary. We are going use the following datasets:

- List of CRAN package, available with function

available.packages(). - List of English words, available at WordNet database. This is a comprehensive database of English words that I once used in a paper. It contains several tables, including all possible words from the English language.

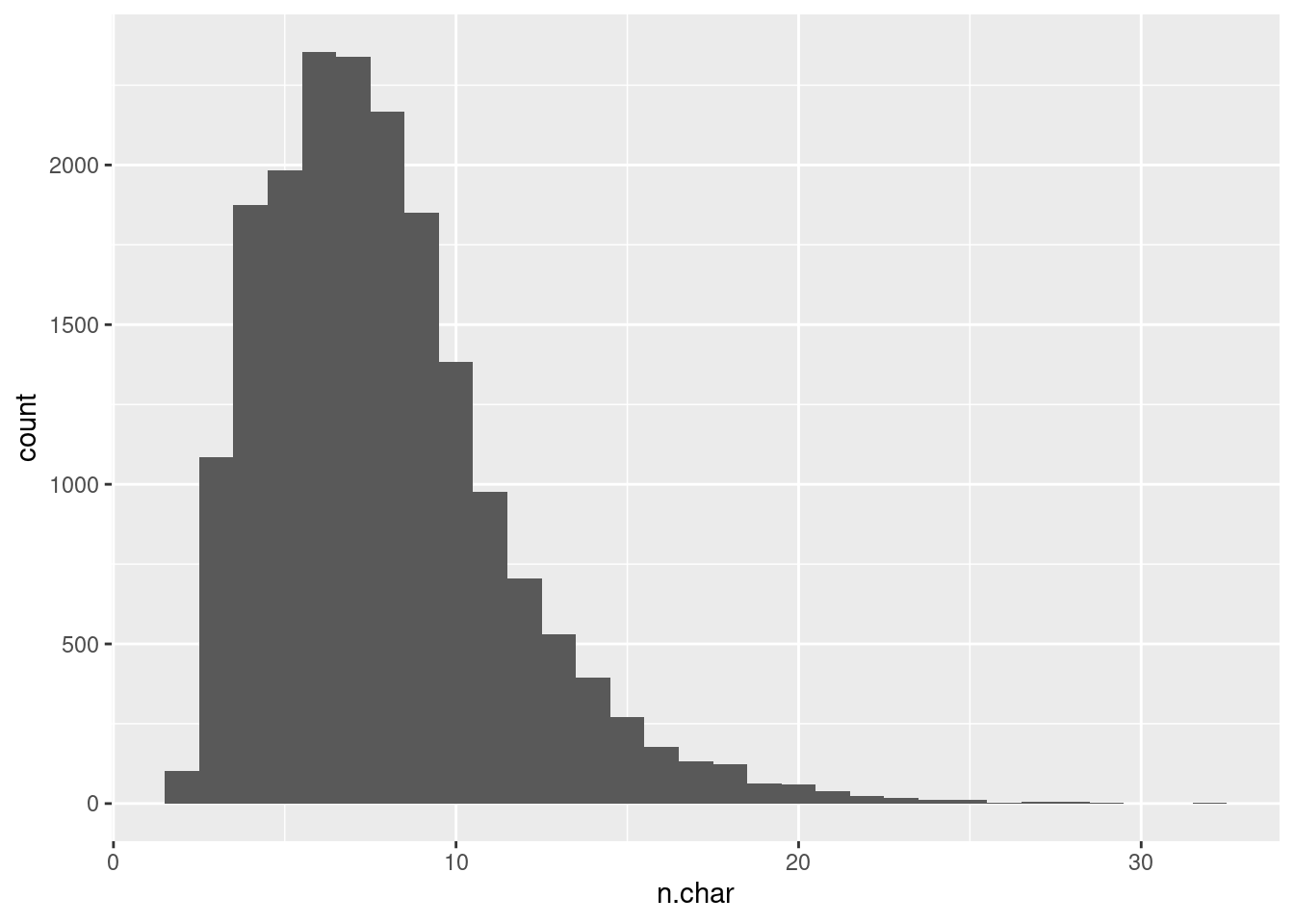

First, let’s have a look at the distribution of size (number of characters) for all packages available in CRAN:

library(dplyr)

library(ggplot2)

# get data

df.pkgs <- as.data.frame(available.packages(repos = 'https://cloud.r-project.org/')) %>%

mutate(Package = as.character(Package),

n.char = nchar(Package)) %>%

rename(pkg = Package) %>%

select(pkg, n.char)

# plot it!

p <- ggplot(df.pkgs, aes(x=n.char)) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 1)

print(p)

As I suspected, the names of CRAN packages are usually small, with an average of 5-6 characters. We have a couple of packages with more than 25 characters. Let’s see their names:

df.pkgs$pkg[df.pkgs$n.char>25]## [1] "AnglerCreelSurveySimulation" "BipartiteModularityMaximization"

## [3] "BoutrosLab.plotting.general" "easyDifferentialGeneCoexpression"

## [5] "factset.analyticsapi.engines" "factset.protobuf.stachextensions"

## [7] "FractalParameterEstimation" "GeneralisedCovarianceMeasure"

## [9] "GreedyExperimentalDesignJARs" "ig.vancouver.2014.topcolour"

## [11] "image.CornerDetectionHarris" "MulvariateRandomForestVarImp"

## [13] "NegativeControlOutcomeAdjustment" "particle.swarm.optimisation"

## [15] "paws.application.integration" "RcmdrPlugin.sutteForecastR"

## [17] "ResidentialEnergyConsumption" "RoughSetKnowledgeReduction"

## [19] "samplesizelogisticcasecontrol" "sarp.snowprofile.alignment"

## [21] "SuperpixelImageSegmentation" "wyz.code.offensiveProgramming"I am sorry for the authors, but, in my opinion, I’m sure we could find better names. I am also sorry for those who are using these packages but do not use the autocomplete tool of RStudio and need to type the loooooooooong names.

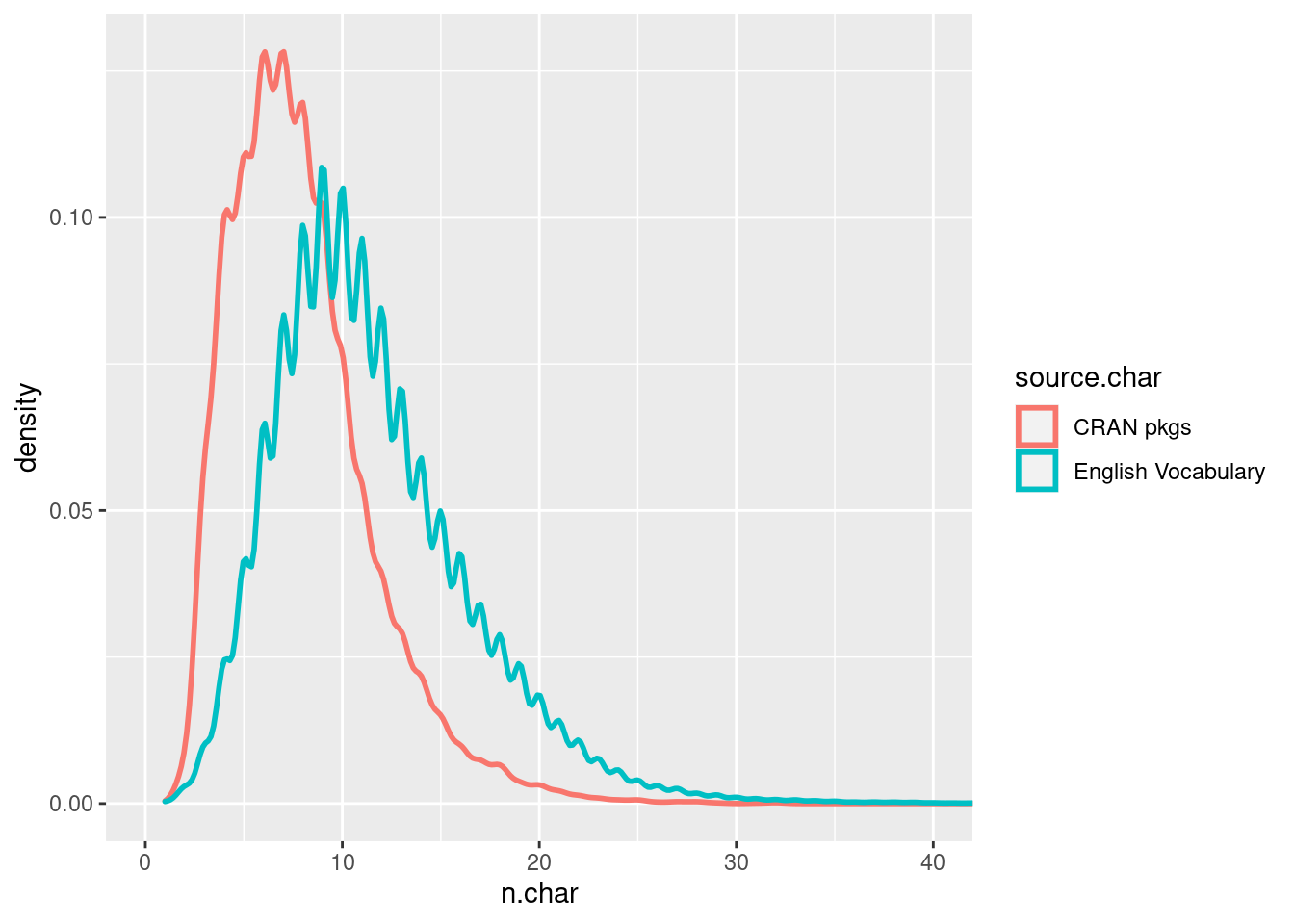

As for my hypothesis that CRAN package have short names, let’s compare the distribution of package names against all words in the English language. For that, let’s load the WordNet database and do some calculations:

library(RSQLite)

library(stringr)

# get data

conn <- dbConnect(drv = SQLite(), 'wordnet/sqlite-31_snapshot.db')

words <- dbReadTable(conn, 'wordsXsensesXsynsets') %>%

select(lemma)

# some are duplicate (same word, different types)

words <- unique(words)

words$nchar <- nchar(words$lemma)

# set df to plot

df.to.plot <- data.frame(n.char = c(df.pkgs$n.char, words$nchar),

source.char = c(rep('CRAN pkgs', nrow(df.pkgs)),

rep('English Vocabulary', nrow(words))))

p <- ggplot(df.to.plot, aes(x=n.char, color=source.char )) +

geom_density(size=1) + coord_cartesian(xlim=c(0, 40))

print(p)

As I suspected, the distributions are very different. There is no need to apply a formal test as the visual evidence is clear: CRAN package have a tendency for shorter names.

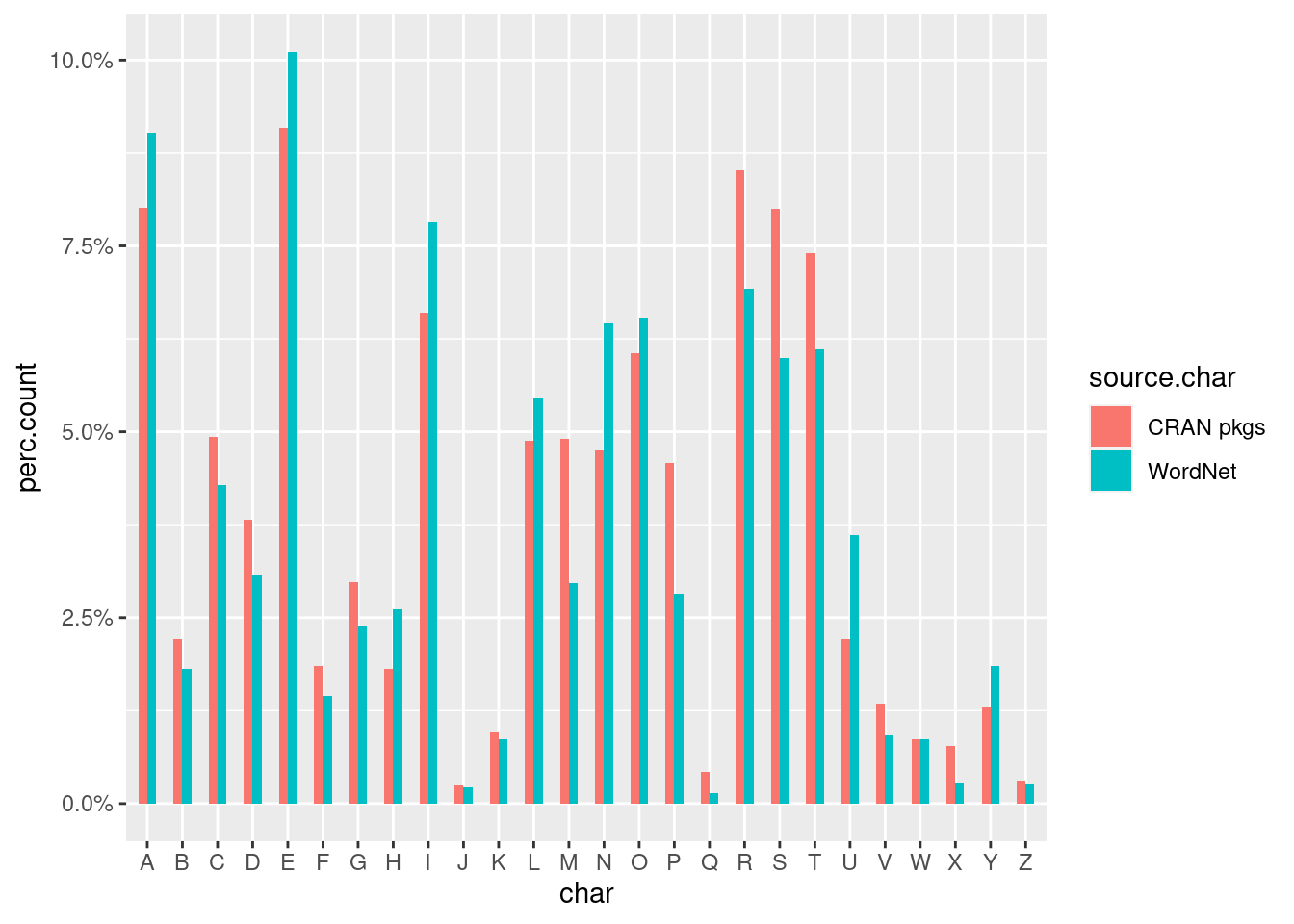

Now, let’s look at the distribution of used letters in relative terms:

library(scales)

temp <- str_split(str_to_upper(df.pkgs$pkg), '')

all.chars <- do.call(what = c,args = temp)

char.counts.pkg <- table(all.chars)

temp <- str_split(str_to_upper(words$lemma), '')

all.chars <- do.call(what = c,args = temp)

char.counts.words <- table(all.chars)

df.to.plot <- data.frame(perc.count = c(char.counts.pkg/sum(char.counts.pkg),

char.counts.words/sum(char.counts.words)),

char = c(names(char.counts.pkg),

names(char.counts.words)),

source.char = c(rep('CRAN pkgs', length(char.counts.pkg)),

rep('WordNet', length(char.counts.words))))

# only keep LETTERS

idx <- df.to.plot$char %in% LETTERS

df.to.plot <- df.to.plot[idx, ]

p <- ggplot(df.to.plot, aes(x=char, y = perc.count, fill=source.char,width=.5)) +

geom_col(position = 'dodge') + scale_y_continuous(labels = percent_format())

print(p)

The result is really interesting! I was expecting far more differences in the relative use of characters. Not surprisingly, letter R is more used in package naming than in the English vocabulary. Still, the difference is not that large. Given that R is the name of the programming language, I was expecting a much greater proportion of R characters. My intuition was clearly wrong! In comparison, letters P and M have more difference in relative terms than letter R. I’m really not sure why that is. Overall, it is pretty clear the use of characters in the names of packages follow the distribution of words in the English language.

While the distribution of letter is similar, we find just a few package with names exactly as in the English language. For all 18699 packages found in CRAN, only 1260 are an exact match of all 146625 unique words in the English vocabulary.

Summing up, our data analysis shows that the names of packages are usually shorter than the words in the English language. However, when looking at distribution of used characters and editing distances, it is pretty clear that the names are based on the English language, usually with a few modifications of a base word.

I hope you enjoyed this post.